INTERVIEWS

ICONS OF PHOTOGRAPHY | ICONIC PHOTOGRAPH: THE KISS

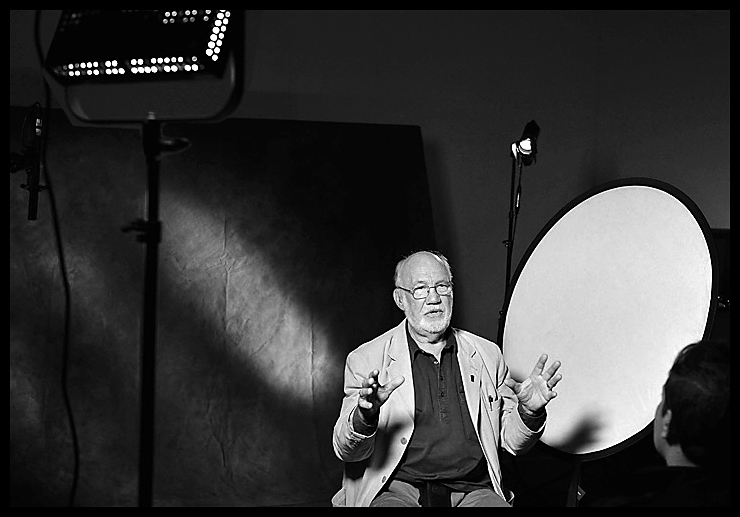

Arthur Steel was one of the very few photographers to capture Charles and Diana’s famous wedding-day kiss. He tells David Clark how he did it.

The apparently ‘fairy-tale’ wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer on 29 July 1981 was enthusiastically celebrated around the world. Approximately 600,000 people lined the wedding route on London’s streets, while an estimated worldwide audience of 750 million people watched events unfold on television. Thirty years on, it remains the most popular television programme ever broadcast.

On the day, hundreds of photographers from national and international newspapers, magazines and media organisations covered the event. Many photographers were positioned outside St Paul’s Cathedral, where the marriage took place.

However, at St Paul’s Charles and Diana seemed too nervous and preoccupied for photographers to capture the spontaneous, joyful images that newspapers wanted. As the day progressed, attention was focused on Buckingham Palace, where the newlyweds were due to appear on the balcony in the afternoon. Among the photographers positioned on the Queen Victoria Memorial, opposite Buckingham Palace, was Photographer Arthur Steel. As one of Fleet Street’s few representatives on Buckingham Palace’s select ‘royal rota’, he was supplying images for all the British daily newspapers.

Arthur was then in his mid-40s and a seasoned press photographer, he was an accomplished all-rounder, experienced in tackling a range of assignments, including hard news stories, celebrity pictures, sport and fashion shoots.

Arthur, now 74, has a clear memory of the day’s events. ‘The authorities had built an enclosure for press photographers on the Victoria Memorial, which consisted of three or four tiers of wooden boards on scaffolding,’ he says. ‘But when I went to choose my spot a couple of days prior to the event, I could see there was a problem’.

Although the boards looked strong, as soon as Arthur walked on them he found that they were very springy. As the photographers would all be shooting with long lenses and resting their tripods on the boards, he realised that camera shake could potentially ruin many of the wedding pictures.

Arthur chose the steadiest available spot, right at the end of one of the higher tiers, surrounded by a corner section. To give better support, he asked a builder friend to lend him a couple of pieces of scaffolding with a ‘coupler’ to join them on to the main scaffolding poles. This scaffolding, topped with a cushion, gave Arthur a much more stable surface on which to rest his camera.

He was shooting with a Leicaflex, a fully manual SLR manufactured by Leitz, which was fitted with an 800mm lens. The lens weighed 7kg and at the time was worth £6,800. As a backup, Arthur also had a Nikon SLR with a 1,000mm lens attached, set up on a tripod. Both cameras were trained on the balcony and he fired them simultaneously using a double cable release.

Although Charles and Diana were not due to appear until after 1pm, the photographers had to be in place by 8am to avoid the crowds. They were stationed on the four-tier enclosure, on the ground and inside the palace forecourt. Arthur was standing next to David Bailey. All the photographers were feeling the pressure. ‘There wasn’t much conversation between us as there was a lot of double-checking of cameras, films and all that sort of thing,’ Arthur says. ‘We were all a bit strung out. I also found that even with the extra scaffolding support, if one of the other photographers coughed or sneezed or made any kind of movement, it could be observed down the lens.’

Around five hours later, Charles and Diana appeared on the balcony to wave to the crowds. They made several appearances on the balcony and every time they went back inside Arthur re-loaded his cameras so he could avoid missing any of the action. The films were collected on an hourly basis by police, who took them through the crowds to a point where despatch riders would collect them and take them to be processed immediately.

However, the photographers were still waiting to capture the one iconic moment that would symbolise the wedding. Then, during one of the balcony appearances, Charles and Diana leaned towards each other and momentarily kissed. It happened only once and was over so quickly that most of the photographers were caught off guard; of the 150 press photographers outside the Palace, only three are known to have captured the kiss.

Arthur knew this would be the picture of the day and when he returned to the offices later in the evening he discovered that it was being used on the majority of the front pages of the major UK newspapers. Arthur had actually shot a wider scene that included other royal family members, but on the front page it was cropped to simply show Charles and Diana’s seemingly passionate kiss. His wily approach and careful planning, combined with his razor-sharp reactions, resulted in him capturing the royal wedding photograph that everyone remembers.

NERVES OF STEEL

In 1989 one of the great newspaper photographers of our time turned his back on Fleet Street to become a recluse. Bob Aylott tracks down Arthur Steel, former Fleet Street lensman, to talk to him about his eventful career

Long nights of drunken talk and arguments about who are the greatest photographers of all time are commonplace in the pubs of Fleet Street. The flies on the walls of The Harrow, The Mucky Duck (now The White Swan) and Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese have heard it all before as the conversation is repeated by generations of photographers.

It was a warm May evening and I was leaning against the bar of the Old Bell enjoying a heated chat with a motley collection of Fleet Street veterans. The rear doors of the public bar were open and the bells at St Brides rang a sobering funereal tune. ‘So, who is Fleet Street’s greatest photographer of all time?’ someone asked. This was a question that required a lot of searching of the grey matter, particularly as we were trying to remember the names of photographers from more than 30 years ago.

By the end of the evening the name Arthur Steel was cropping up more than many better-known photographers. Then someone asked, ‘Whatever happened to Arthur?’

After a lifetime of great pictures, the stresses and strains of Fleet Street paid havoc with Arthur’s health and he took early retirement in 1989. With his Geordie wit and Irish charm, he became a self-styled recluse – in Wimbledon, Southwest London.

Fast forward a few months and I am waiting for Arthur outside Wimbledon Station. Suddenly a black 1953 vintage Riley RMF screeches to a halt, the passenger door swings open and Arthur’s voice screams, ‘Get in, get in.’ With rubber burning, the shining beauty roars away and we jump a red light. ‘How can you be a recluse driving a car like this?’ I ask. Arthur smiles and turns left. ‘People are always waving at me, and I wave back, but at least I don’t have to talk to them,’ he says. Arthur points out a new dent in the nearside wing. ‘I’ve just done that coming to pick you up,’ he says. I try to look apologetic, although it is not my fault that he crashed into a pillar. ‘I won’t get it mended,’ he adds, ‘as it will remind me of you.’

Passing through an amber traffic light triggers another motoring memory for my 68-year-old recluse. ‘I drove around the Aldwych in the City the wrong way, ran three red lights and was the first photographer at the scene of the Shepherd’s Bush police murders. I even beat Terry Fincher [the Daily Express photographer] on that story,’ he recalls of the day in August 1966 when three London policemen were shot dead by Harry Roberts.

‘It was a world exclusive,’ he says, proudly. ‘There were two bodies lying uncovered in the street, and the third was still in the car. I hastily went round the back, into a house and up the stairs to a bedroom. I was taking pictures of one of the bodies from a first-floor bedroom window when I heard footsteps coming up the stairs. I thought it was a copper coming up to stop me photographing the scene. I quickly took the film out of the camera [a Nikon F with 105mm lens] and hid the roll down my sock. It was a great news picture on the day, as it showed the body stretched out with police chiefs looking down at it. However, it was Fincher, not the police, running up the stairs, and just as he reached the window they covered the body with a blanket.’

Arthur’s childhood was unusual for a man who would eventually tread the Fleet Street path. It was while training to become a priest in Durham that the 12-year-old first discovered the delights of photography. Returning home to Newcastle for a Christmas holiday, he was given a box camera as a present by his parents. Arthur clearly remembers that his first photographs were taken at his priests’ college, but because of the high price of film he couldn’t afford to take many pictures and became very selective.

‘I would spend hours looking through the viewfinder composing pictures that I never took,’ he says. ‘I only pressed the button if it was something important like the football team group, and then it would be only one exposure. When the film was full, which could take months, I’d get it developed. The practice of being frugal with film has followed me all through my life, and waiting for the one shot that matters has paid off many times on the big jobs.’

By the age of 15, Arthur decided that the priesthood was not for him. He worked for a short time as a trainee accountant on the Newcastle Evening Chronicle. Six months later he landed the job as trainee photographer on the Chronicle, beating 400 other applicants for the position.

For this 16-year-old choirboy, who had failed his 11-plus but could speak Latin, Greek and French, these were the first steps on the road to Fleet Street.

As a trainee photographer, much of Arthur’s time was spent in the darkroom. It was only on rare occasions that he was allowed out with a camera on his own. However, his first assignment, with the chance to take a real news picture, turned into a disaster.

‘The demolition boys in South Shields were in the process of knocking down one of the tallest chimneys in the country,’ explains Arthur. ‘The chief photographer had been given the job on the first day, but he soon got bored sitting around waiting for this thing to topple. So his deputy was given the job the next day, but he got bored as well. After that a different photographer was sent to watch and wait. In the end nobody wanted to know about this story. The chimney was still standing and the workmen still taking out bricks around the base and inserting wood posts.

‘Then, a week later, the picture editor sent me to cover the chimney site. I had an old plate camera with a focal-plane shutter that you changed the exposure by the width of the slit in the cloth blind. I had been sitting around from morning to night watching the workmen banging around at the bottom of the chimney. As evening approached the light got worse and I needed to open up my blind for the correct exposure. I was with all the other local newspaper photographers, but didn’t really communicate with them as I was just a lad from the darkroom in Newcastle.

‘Then two policemen came over and told us that the workmen were having a break, so we could all relax for 20 minutes or so and have a cup of tea. I thought this was the ideal time to adjust the slit to a wider opening. I removed the glass plate and placed the camera on my lap to adjust the opening of the blind, when suddenly the chimney comes down like a bat out of hell. I was in a state of shock. All I could see was a big cloud of dust as I was trying to get the glass plate back into the camera. That was a big lesson for me, and from that day on I made sure I have never missed another picture,’ he says confidently.

In a career that lasted almost 40 years, the gentle giant from Newcastle never did miss another important picture – and he took an incredible number of stunning images. In fact, two of his photographs will go down as classics in the history of British press photography – the picture of Harold and Mary Wilson sleeping in 1970 and the royal kiss picture of Charles and Diana on their wedding day in 1981.

Arthur stayed with the Newcastle Evening Chronicle until the early ‘60s. Even though he was shooting local social features on days off with his picture editor Peter Crookston, Arthur knew that it was time to move on. He felt he’d exhausted the potential of the regional paper, and wanted to cover bigger and more exciting assignments.

Still a shy young man, Arthur took a correspondence course in the art of self-confidence and then wrote to every Fleet Street editor asking for a job. He had three replies, three interviews and job offers from the Daily Mirror, the Daily Express and the Daily Herald. He accepted the job on the Herald (which eventually became The Sun, owned by Rupert Murdoch) and joined as a staff photographer.

While covering the 1970 general election for The Sun, Arthur took the photograph that many experts call the best political news picture ever. He settles back to explain the story behind the remarkable image.

Arthur had travelled by train to Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s Huyton constituency in Merseyside. His brief was to follow the PM around on election night. ‘I stuck to Wilson like a rash, and wherever he went I would follow,’ says Arthur. ‘Late into the night it was clear that he had lost and Edward Heath would be forming the next government. I was booked into a hotel and ready for my bed when Len Hickman, the picture editor, phoned to say that he wanted me to return to London’s Downing Street.’

Arthur got a lift with Daily Express photographer Brian Duff in his chauffeur-driven office car, and together they joined Wilson’s motorcade as he returned to London.

‘There were police motorcycle outriders at the front, then a police car, the Wilson’s Rover, followed by more police cars, Labour Party officials, TV and press with two more police motorcycle riders at the rear. It was a motorcade of 13 or 14 cars,’ says Arthur. ‘We were about three cars back from Wilson’s car and as dawn was breaking I could make out Harold and his wife Mary slumped together on the back seat. I assumed they were resting or asleep. There was the chance of a good picture, but we had to move fast. The motorcade was travelling at 70mph and approaching the last few miles of the M1. If we didn’t move quickly, the picture would be lost.

‘Brian and I got into a position in the back of the car with our cameras pointing through the open window. Our driver pulled out from the convoy and into the central lane. He put his foot down and accelerated until he was alongside Wilson’s car. He tried to synchronise his speed to make it easier for us shooting at slow shutter speeds.

‘The trouble was that he shot past Wilson’s car too quickly. We only had time to expose one frame each, then our driver accelerated even faster to get well in front and escape the police. Luckily we were close to the Scratchwood service station exit, so we pulled off. From there we could see the chaos that we had left behind. The whole convoy had come to a grinding halt and had parked on the hard shoulder. The cops were all over the place and some were talking to Wilson. All hell had broken loose,’ adds Arthur with a twinkle in his eyes. ‘I was so close I could have shot him.’

So did Arthur know he had the picture? He breaks into a smile and says, ‘Deep down I knew that I had it, because I always feel comfortable with the Leica M4. When you press the button on that camera, you know you’ve got the picture in the bag.’

Arthur and Brian let the convoy pass the service station and then rejoined it at the rear for the short journey to Central London. Both photographers had fired off just one frame. Brian’s view of Harold and Mary was obscured by the window bar and unusable. Arthur’s had the Wilsons near the edge of the negative, but it was clear and showed the election losers fast asleep. ‘As a news picture, I regard it as a great achievement,’ continues Arthur. ‘It was shot under difficult circumstances: dawn had just broken and the light was bad; we were travelling at 70mph; and the exposure was a 1/30sec at f/1.4 on a 35mm lens through a car window. It was a thin negative even though I had asked the darkroom to give the film extra development. Unfortunately Brian didn’t get the shot, but to be fair to him he never asked me to share my picture.’

After the film was processed and the negative printed, Arthur was sent to Downing Street to cover the rest of the day’s political comings and goings. Arthur explains: ‘Downing Street was overflowing with 300 photographers and TV crews. I hadn’t slept for 24 hours and I was knackered. Suddenly this “Mrs Mop” starts to sweep up the dirt on the steps of No 10. I was half-asleep and I was still the only photographer who took the picture.’ Incredibly, a cleaner has never been photographed on the steps since.

The royal wedding of Charles and Diana on 29 July 1981 gave Arthur another memorable photograph. Surrounded by hundreds of other photographers, it was his picture of ‘The Kiss’ that beat the best of the rest and went around the world. It was also listed on AP (25 December 1999) as one of the top pictures of the 20th century.

Working from a wobbly press stand on the ‘Wedding Cake’ [the white marble monument built to honour Queen Victoria opposite Buckingham Palace], Arthur was knee-deep in photographers covering the big day. From the rota-pooled position, his pictures would be shared with all British newspapers. ‘The stand was constructed so badly that if anyone coughed, our tripods and cameras would shake about so much that it was impossible to work on extreme long lenses,’ Arthur explains.

Using heavy tripods and clamps, Arthur bolted his two cameras together onto the scaffold poles at the very end stand. They were aimed and pre-focused on the balcony where the newlyweds and the royal family were due to appear. Arthur had a Leicaflex SL2 with a 800mm f/6.3 lens and a Nikon F3 body with a 1000mm f/11 mirror lens, while the film was Kodak Tri-X rated at ISO 400. The cameras shared a joint shutter cable release giving Arthur two identical negatives on slightly different focal-length lenses. Arthur found himself standing next to social snapper David Bailey. Arthur recalls, ‘Bailey had his posh lunch hamper and bottles of wine, while I had f*** all and he didn’t even offer me his crumbs.’ Luckily that day Arthur was only hungry for success as he photographed the happy couple. He continues, ‘They [Charles and Diana] would wave to the crowd and disappear. Then they would come back and do it all over again several times. Each time they disappeared I would quickly change film in both cameras, even though I had shot maybe only ten frames. Most of the photographers didn’t bother changing films – they waited until they ran out. I was using my motordrive on single frame. The kiss happened so fast, that if you were working with a motordrive set on continuous you could have easily have missed the moment. You may have caught them moving together, or moving away, as the kiss was nothing more than a peck. A lot of photographers were changing film, others were getting bored with it all, while the rest just completely missed it. There were reporters and TV crews who never saw a thing.’

Two other photographers who were lucky on the day were Ron Burton from the Daily Mirror, who captured the kiss from another rota position, and Alisdair Macdonald, also from the Daily Mirror, who got the picture from a non-rota position at street level. However, it was Arthur’s picture that recorded the romantic moment perfectly. He had fired only one frame simultaneously on each of the cameras, but strangely the negative shot on the Nikon vanished back in the office. ‘I sent the two films back to The Sun darkroom, and never ever saw the second negative,’ he says. ‘Apparently, when the picture editor Kelvin McKenzie, saw the picture, he cartwheeled down the complete length of the editorial floor. Now that’s one picture I would have loved to have taken.’

‘I was in shock. All I could see was a big cloud of dust as I was trying to get the glass plate back into the camera. That was a big lesson, and from that day on I made sure I have never missed another picture’

‘Apparently, when the newspaper editor Kelvin McKenzie saw the picture [the Charles and Di kiss], he cartwheeled the complete length of the editorial floor’

THE ZOO GANG

On quiet news days, Fleet Street’s hotshots would head for the zoo in search of pictures with the ‘Ah…’ factor. Former professional photographer Arthur Steel feeds Bob Aylott a few titbits about photographing the animal kingdom.

It’s on those balmy summer days when the news is slow that the country’s top photographers rush to the zoo in search of an alternative front-page picture. It could be a cute baby animal or a classic hot-weather picture that will keep their editors happy. Under the shade of many an ornamental palm tree I have seen Fleet Street’s finest crumble at the sight of a new baby kangaroo, giraffe or tamarin. Even a giant rhino being hosed down by its keeper or a penguin basking in the sunshine could tickle the fancy of the hard-nosed photographers.

Shooting animal pictures with the ‘Ah…’ factor is another aspect of press photography that is as important as the big news jobs. In zoos around the country I have mixed with the photographers known in the business as ‘The Zoo Gang’. Arthur Sidey from the Daily Mirror and Mike Hollist from the Daily Mail were two of Britain’s best-known and best-loved animal photographers of their day. When the world’s trouble spots had quiet periods, these photographers would be joined by the likes of Terry Fincher and Bill Lovelace from the Daily Express, and all would be hunting for that offbeat picture to fill a large hole in the paper. Today, though, I am in Wimbledon, Southwest London, to talk to former professional photographer Arthur Steel about how he produced animal pictures that had the readers cooing over their cornflakes.

‘I have always loved animals,’ says Arthur with a smile. ‘I was brought up with pets, and as a child I always had a cat or a dog. It’s their honesty, simplicity and beauty that I adore. I love them because I don’t have to talk to them. I have patience with animals that I don’t have with humans. I realise that they won’t stand on their heads when I want them to, but I can spend hours, days or even weeks waiting for that moment when they eventually do something to make a decent picture.’

As he stops to catch his breath, and with the animal PR puff over, I ask 68-year-old Arthur why his famous picture of nine dogs watching a television set is not quite what it seems – because eight of the dogs were stuffed! Like an embarrassed schoolboy caught with a copy of Playboy, he bursts into nervous laughter. ‘Oh, you know about that picture,’ he says. ‘I have been a bit of a cheat in the past.’

Arthur quickly changes the subject and tells me about his first animal picture. It was taken while he was on national service in Shropshire in 1956. Using a home-made camera that he had built in the style of a Speed Graphic, Arthur photographed a young gosling coming out of his army boot. He then sent the glass plate to the Evening Chronicle in Newcastle, where it was published. ‘That helped me get through my national service, because I knew that I could go back to photography when I got out,’ he says. From these humble beginnings, Arthur would eventually go on to become one of the country’s top photographers.

Newspaper editors either love or hate animal pictures, such as the colourful, but animal-picture-hating Kelvin McKenzie, Arthur’s pictures used to end up in the bin. This restricted him to shooting on his days off, but under the terms of his contract he would have to first offer his animal crackers to picture editor. Then, once they had been rejected, he was free to sell them to the highest bidder.

A cute animal picture not only brings a smile to the readers’ faces, but it can also help place unwanted pets into loving new homes. Arthur explains the power of the printed picture after his photographs of a Newcastle cat-and-dog shelter were used in the Evening Chronicle. ‘It was a picture of three lonely-looking dogs behind wire mesh that did it,’ he says. ‘The response from the public was so great that 30 dogs and all the cats in the centre were given homes by the public.’

However, it’s not all happy endings in the wonderful world of animal magic, as Arthur recalls an encounter with a notorious gorilla at London Zoo more than 25 years ago. ‘All the photographers knew about this particular gorilla,’ he explains. ‘For some unknown reason it disliked gentlemen from Africa. The gorilla would collect up handfuls of its droppings, wait for African men to appear and then throw the manure at them.

‘Big trouble loomed when the Duke of Edinburgh visited the zoo with an important African dignitary. Officials had taken the precaution of placing chicken wire between the gorilla and the important visitors. What they hadn’t bargained for, though, was the fact that this famous gorilla had got wind of all of the pomp and pageantry, and wanted to be part of the action. The animal liquidised its droppings with its urine and, at exactly the right moment, hurled a handful of the runny stuff through the wire mesh. It just missed Prince Philip, but covered the African dignitary,’ adds Arthur with a grin.

Photographers know that they should never work with animals or children, but Arthur explains the amazing financial advantages of shooting good animal pictures. ‘I can shoot an animal picture today and make good sales, then in five years’ time re-issue the same picture and earn good money again,’ he says. ‘And that picture will still be selling in 50 years’ time. A picture of a monkey taken in the 1950s looks the same as a monkey today. Unlike people pictures, where the fashions change, animals don’t change with time. They are also universal, so you can sell your pictures around the world. I’ve got animal photographs that have been selling constantly in libraries for decades and it makes no difference to sales whether they are in black & white or colour.’

One talent that is essential if you are to rule the animal kingdom with your camera is the patience to sit things out and be able to hover like a hawk waiting to pounce on your prey. ‘With animals it is a waiting game,’ says Arthur.

I tell him this is all highly commendable but what about the picture with the stuffed dogs? What does he do when the live animals don’t produce that winning picture? Arthur lets me into his secrets of success.

‘I was amazed to discover shops in London that hire stuffed animals,’ he explains. ‘I can hire anything, from a mouse to a hippopotamus, and it’s big business for the advertising agencies. So when I thought of this picture of the dogs watching the television, I knew they had to be stuffed. There was no way I could have controlled a large pack of live dogs and be able to get them all watching the screen at the same time. So I hired eight dogs, with the ninth one being mine and that was well and truly alive at the time of shooting.’

‘The Mail on Sunday’s You Magazine bought the first British rights,’ he explains. ‘John Lyth, the picture editor, fell hook, line and sinker for it. A few months later I shot a photograph of a real cat looking down at a stuffed mouse. I sent John the picture and he phoned to say he loved it, but asked if the cat was stuffed. “No, it isn’t, but the mouse is,” I told him. “Oh, I never use stuffed animal pictures,” he replied. I didn’t have the heart to tell him about the picture of the dogs he had just published.’

As a professional photographer, Arthur has always considered the use of stuffed animals as an acceptable part of the job. ‘As long as people get pleasure in looking at the pictures, there is nothing wrong,’ he says. ‘Providing they have been photographed realistically, no one is any the wiser. I’m not going to put a stuffed hippo on a diving board down at the local baths, because that’s ridiculous,’ he says with conviction, and then tells me about a famous photographer who used to submerge cats in bowls of custard so he could get pictures of them licking their lips. ‘I don’t do anything like that,’ he adds. ‘I would never risk harming any animal, not even a stuffed one.’

‘Unlike people pictures, where the fashions change, animals don’t change with time’

COMIC STRIPS

Former professional photographer Arthur Steel reveals how he shot his funny photographs.

If you thought press photography was all about jumping on planes and covering the world’s trouble spots, think again. It’s not only dodging bombs and bullets that makes a top operator, as there is another talent that is needed to survive in the toughest job in photography.

If the editor hasn’t got a picture that makes his readers cry, then he’ll want one to make them laugh. Either way, he’ll get his tears at the end of the day, so it is the funny side of life that the photographer must be able to find and capture on a slow news day.

Today I’m back in Wimbledon with the former professional photographer Arthur Steel to discover how he cracked those quiet days on the country’s biggest-selling tabloid. Last month we looked at the gritty side of his 40-year career and now we can enjoy some of the pictures that have brought a smile to millions of readers.

As a young photographer with the Newcastle Evening Chronicle, Arthur would be sent out roaming to find offbeat pictures to fill holes in the newspaper. He explains, ‘It could be a pretty local landscape – not that there were many of those in Newcastle in the 1950s – or in my case I would look for a funny or unusual picture.’ He admits that if his name were on the photographers list with the word ‘roaming’ alongside it, he would be worried. ‘I was terrified in the beginning, but it was good training in the long run,’ he says.

Arthur also studied Picture Post and photographic magazines for new ideas and to see how other photographers worked. ‘The more magazines I looked at, the easier it became for my eyes to see pictures,’ he says. ‘I have always been able to appreciate the funny side of life. I would love to say that it is a gift, but it comes from all that roaming I did in Newcastle. I was desperate to return to the office with a good photograph. I would never forget that you are only as good as your last picture. I am a natural worrier, terrified of failing and desperate to win.’ He pauses, before adding, ‘It’s because I’m a Sagittarian.’

This afterthought triggers memories of an encounter with another Sagittarian, cricket legend Ian Botham. Arthur was in Scotland to photograph Ian salmon fishing in 1980. Once the pictures had been taken, the pair were ready to play some serious bar-room pool. ‘Sagittarians have to win, but Ian’s a tough character; he is also twice as big as me and doesn’t like to lose’ says Arthur. ‘He challenged me to a game. I’m no pool player, but if someone makes a challenge, I have to accept and I have to win. The problem was that Ian is exactly the same.’

The pair agreed on a £1 bet on the first game and from there the evening developed into a drunken rivalry of missed pots, skewed shots and skied balls – at least on Botham’s part. ‘I won the first game, but I put that down to the amount of alcohol Ian was drinking,’ Arthur recalls. ‘He had a greater capacity than me for booze, but I could tell it was affecting his game. Not happy with losing he made it double or quits on the next game, and the next and the next, and so on. I found every game easier than the last. He wouldn’t give up and the games went on all night until we both passed out through tiredness,’ he smiled. ‘I don’t remember collecting my winnings, but it was one hell of an experience.’

Arthur’s approach to shooting humour is simple. ‘I tend to think of it as opposites, like tall and short,’ he explains. ‘I remember seeing Elliott Erwitt pictures of small dogs and big dogs which inspired me, and I started to explore that avenue. There are two types of funnies – the ones that just happen, and the ones that are set up to look as if they have just happened. The art is stunting up pictures that look natural. Some photographers have a problem stunting up pictures, but I don’t. I can think about pictures for months in advance, while at other times it could all happen in an instant.’

He tells me about the day in July 1969 when man landed on the moon. ‘The front pages of all the newspapers showed photographs of footprints on the surface of the moon,’ says Arthur. ‘I looked at these remarkable images and knew that I could shoot the same picture in London.’ Living in Fulham at the time, Arthur often took his children to a sandpit in Bishop’s Park. This was the location he decided to use for the picture. ‘I just walked on the sand and stuck a small Union Jack flag in the sand. My picture was almost identical to the one from the moon without any of the expense,’ he smiles. ‘The newspaper used it across a whole page with the headline “Bishop’s Park Yesterday” picture by Arthur Steel.’

Another of his early humour pictures shows a line of front doors with two milk bottles waiting to be picked up. Arthur tells me it was in the days when builders used rows of old doors joined together as a screen to their site. The idea for the picture came as he passed the site while driving to work. ‘Originally I was thinking of painting one of the doors with a colourful gloss paint, leaving the rest old and peeling, but the two milk bottles idea won the day,’ he explains.

Another classic picture also happened as Arthur drove to work in Fleet Street. ‘I would pass St Thomas’s hospital and watch the old place gradually being demolished. At the end there was a lone workman with a sledgehammer walking about on the top of an enormous pile of rubble. I came to a screaming halt, dumped the car and rushed over to the site. I gave the chap a fiver and set up the picture,’ he says. ‘You see, the art in all of this is not only thinking and seeing pictures, but also making them work. It’s getting the workman in the right position, making sure that Big Ben was in the background and using the right lens for the shot. The simple pictures always work the best.’

Turning his attention to yet another funny shot, Arthur says: ‘The chap on the hay cart happened to be passing my wife’s family house in Ireland. The driver was sitting up, but he was happy to lie down. It took about two seconds and resulted a good picture.’

Another secret of Arthur’s success is having a loft stuffed to the rafters with accessories and clothes he has collected over the years. ‘I’ve got a Guardsman’s uniform, bearskin hats, policeman helmets and outfits of every kind that you can think of. I even have a suit of armour and traffic warden uniforms. I have collected everything I could get my hands on, including clerical outfits over the years. It’s like a fancy dress shop up there,’ he grins.

Before I leave Wimbledon, there is one last picture I need to know about. It is the Downing Street snowman of 1968. ‘I was driving home at around 2am after a night shift, when suddenly I saw this snowman outside Number 10,’ he says.

‘But Arthur, it’s wearing your woolly hat and smoking your pipe,’ I say.

‘Oh,’ he replies slyly. ‘So it is.’

‘The art is not only thinking and seeing pictures, but also making them work’

‘I would never forget that you are only as good as your last picture’

Recent Comments